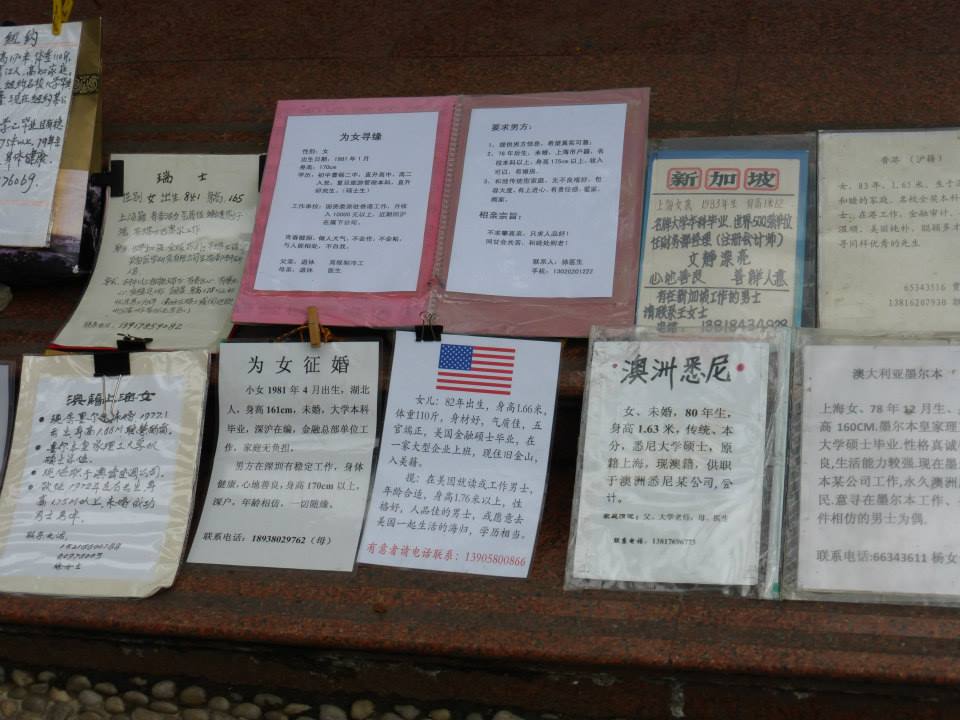

In perfectly straight rows, tables were lined up throughout the park. People strolled among the tables and vendors on this sunny day, casually stopping to read the placards all in Chinese with photos of young men and women. Some tables hoisted American flags, others proudly displayed Chinese fans or prayer beads.

As my favorite travel activity, I was excited to explore another market in Shanghai. Unlike the wet market tour I had recently attended, though, this market wasn’t selling fruits and vegetables. These vendors weren’t seasoned in sales of meat and spices. These vendors had another product to bargain with this day: their sons and daughters.

Welcome to a Chinese marriage market

In a nearby park each Saturday morning, parents and matchmakers set up booths to potentially arrange the marriages of their adult children. A placard for each potential candidate with a photo is set out among tables for shoppers (typically, this market is exclusive to only parent shoppers) to inspect. On the card are the stats of the potential bride or groom: age, weight, height, education, occupation, etc. The American flags indicate the candidate currently resides in the U.S. Parents stroll through reviewing each placard. When they find one that is appealing, they then begin negotiations with the other parents or matchmaker to set up a meeting between the children.

We mainly saw candidates in their late 20s to early 30s, but there was a section of the park for more senior bachelors and bachelorettes. I believe these are typically widowers and widows looking for another chance at love (or partnership). I have also been told about a fake marriage market where the LGBT population can find an opposite-sex partner for the sole purpose of producing a child or, at least, pleasing parents.

As with most forms of traditions, the ancient practice of arranged marriage has evolved here in China. In times past, arranged marriage was a strict policy that may have meant you didn’t even meet your spouse until your wedding day. Today, though parents still have a hand in marriage, it is much more open to one’s free choice. The Chinese marriage market now serves as more of a dating site administered by parents than a rock-solid contract enforced by parents.

Crossing the line?

Since visiting the market, Chris and I have been revisiting a debate. When does culture cross the line? When are acts “just part of the culture” and when should they be viewed as morally offensive?

I believe that Chris and I are very tolerant people, and we do our best to respect other cultures. We both agree the Chinese marriage market, especially in its current form, is just part of the culture. Though it may be strange to our Western senses, this is what is normal and acceptable here.

When more serious events take place, though, what then? When I was an undergrad working toward my minor in Political Science, I took a Global Issues class where I wrote a paper on government involvement to stop crimes against humanity. My specific focus was if practicing female genital mutilation in African countries was a human rights violation or if attempting to intervene was a state sovereignty violation since this was part of the culture. My argument was against FGM for its torturous harm to human beings, regardless of tradition, without the capability to consent.

In the news, we consistently hear about customs that may not only be strange to us but offend us to the point of action. Where do you draw that line and say “that’s beyond acceptable for the culture of the human race?” In my opinion, it’s anything that harms another living creature without consent. When a being is not given the choice of whether to participate, then the cultural aspect becomes morally offensive to the point of protest on others.

Chris and I would love to hear your opinion on the subject. When does culture cross the line for you?

-Monica